Restoration

I had first come across The Braes in the early 1990’s when out bushwalking down in the valley beyond Everglades and came across the Gordon Falls. I decided as an adventure to follow the water course up from the valley, which led to the south-eastern corner of The Braes. The property looked uninhabited, overgrown, and overshadowed by a dense forest.

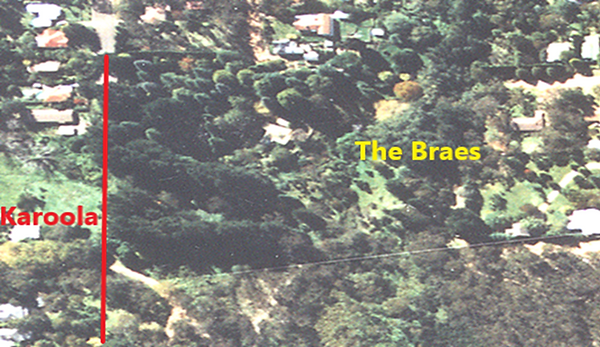

Aerial photo of The Braes in the mid 1990’s overgrown with Radiata Pines

In early 1996 our family acquired the property. We were all enthusiastic and ready to embark on a program of restoration. We entered the adventure with our eyes wide open, believing that with several acres of opportunity and a site with considerable undulation and free-flowing creeks, we had arrived in nirvana and would be able to proceed on a restoration project which was likely to garner considerable support with “locals”.

While the initial task facing our family was site remediation which took place over the late 1990s and in the first decade of the 21st century, our primary focus was on the creation of a cool climate garden which was to reflect the Sorensen philosophy and incorporate a diversity of tree and shrub planting. As our family home and garden, it has many of the botanic features highlighted in Sorensen’s work across the state from the 1930s through to the 1970s.

However, turning an overgrown wasteland, classified as having heritage value, due to the engagement of Paul Sorensen in the 1940s, into a garden reflective of the then, owner, and Sorensen’s aspirations, brought many unanticipated complexities influenced by local government planning guidelines and regulations and the varying expectations of local residents.

Issues encountered:

Blue Mountains City Council (BMCC) approval for removal of plants regarded as noxious by NSW National Parks (final approval taking several years);

BMCC approval of tree removal beyond the Sorensen garden perimeter at the time of its Heritage classification;

BMCC approval of boundary planting;

Management of neighbourhood misinformation;

BMCC planning and heritage asset regulatory guidelines;

Dealing with BMCC regarding the hanging swamp classification and urban runoff mitigation;

Tree Removal

Given the size of The Braes, our journey was particularly onerous, as the property was overgrown.The site was densely populated with more than 200 Radiata pines, Lawson pines, poplar, and other species. Consequently, many of the present species had not developed satisfactorily because of the dense proximity of the trees which had naturally seeded over the past fifty years, as seen below.

The Radiata pine (Pinus Radiata) were planted in their thousands by early nostalgic settlers, especially in the townships and gardens of the Southern Highlands and the Blue Mountains. Research conducted by the National Park on Radiata pines acknowledged this species as a noxious weed and with local council collaboration were encouraged to remove them. It likewise clearly established that the Radiata pine has a distinctly unfriendly habit of poisoning the land adjacent to it, with acid residue and tends to prolong dampness.

In the National Park’s view their useful life expectancy was 50 years, and their removal allowed for more picturesque deciduous trees to flourish and hopefully encourage the planting of a wider variety of trees in climates such as the Southern Highlands and the Blue Mountains.

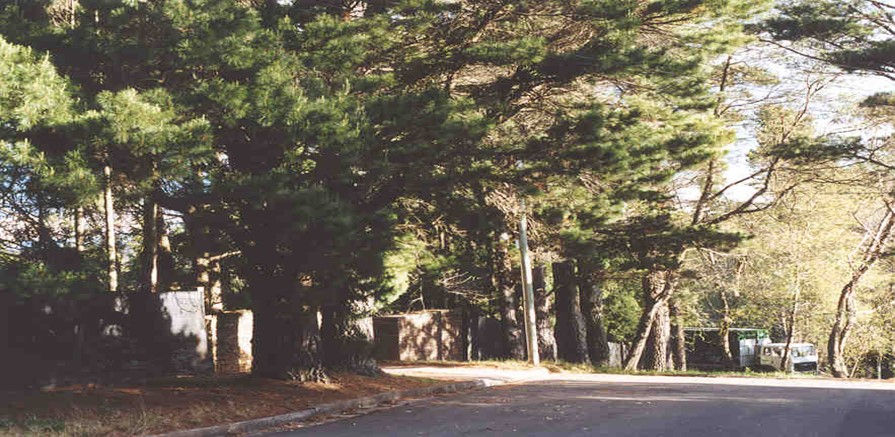

But it was no mean feat to remove the 200+ pines growing on The Braes. Covering much of the property and lining the boundary on Grose Street, the Radiata Pines created a dense forest, restricting progress of other growth.

The photograph to the right provides an illustration of the appearance of the property, Grose Street, and adjacent Karoola at the time of our acquisition.

Heavy machinery was purchased and brought on to the property to enable the safe and efficient removal of the pines, some of which towered up to 20 metres high.

The wood harnessed from the removal of these pines was then recycled and used as posts for fencing along the border of the property to mitigate foxes.

Urban Runoff

Similarly, dealing with urban runoff became a priority, in terms of the remediation of the site. The waterways were clogged with the neighbourhood’s garden cuttings which had cascaded from adjacent streets in Leura, together with rotting vegetation, soil and building waste. The following image depicts the cleaning out of waste material from the dam.

Dredging and cleaning of waste materials in the dam, 1997

Heavy rains in the early years of our occupancy led us to accepts that we needed to do a lot of work and as part of this process, considerable drilling was undertaken onsite to identify ground waters and future potential challenges in relation to managing urban runoff. With independent advice and guidance, including structural and construction engineers, we commenced the process of endeavouring to mitigate unmanaged urban runoff, investing hundreds of thousands of dollars in drainage, flood mitigation and related works.

We also sought advice of a highly experienced surveyor to both define the boundaries accurately and provide guidance in relation to the slope of the land which varied across all segments of the site, as we commenced the journey of restoration.

We observed a channel on the southern boundary of the property which meandered into The Braes from Council land and the National Park which also created swampy conditions in sections of that boundary. The channel took water into the Gordon Creek which then flowed down to Lyrebird Dell and the Gordon Falls. Some of our initial work reinstated the boundary, creating a more stable channel from Lone Pine Ave and Council land. This ensured that waters during heavy storms had an ideal channel into the creek flowing through into the National Park.

BMCC and Karoola’s owners to the west invested time and money in providing a rock foundation to the original channel for the water to facilitate that outcome, diverting urban runoff from Lone Pine Ave which fed into The Braes western boundary creek joining the Gordon Creek immediately prior to entering the national park in the south-eastern section of The Braes.

The work that both parties undertook has been of significant benefit in the remediation of those sections where the properties had a degree of swamp-like adjacency.

The photographs below show the border between the two properties before and after remediation of the site.

Dry Stone Wall & Terracing

Along with the progressive planning for tree and shrub relocation, and the acquisition of Sorensen-recommended plants the shaping of the terraces across the Braes site was a significant part of the garden renewal. Dry stone walls, bridges, and terracing built using European techniques which has survived for centuries make a visual statement across the gardens, as evidenced below:

The Braes Heritage Restoration

In the late 1990’s we commissioned a heritage architect, who assisted in the preparation of an initial heritage report, a conservation management report, and a site management report. These were compiled as we prepared to review the limited built environment on the site at the knoll and the ultimate development of the family home; together with the terracing and structuring of the garden. This reflected the intent which we perceived to be behind Sorensen’s earliest designs around the knoll and the entrance to the property off Grose Street in the north-western corner of the site.

Challenges

Notwithstanding the comprehensive and scientifically based plant regeneration policy determined by the National Parks, in the late 1990s we continued to be faced with several local government challenges including:

dealing with NSW State Government in relation to compliance with planning instruments, National Parks, heritage obligations, as well as the Department of Fisheries and other State Government officials introduced by BMCC; and

assembling a team of advisors including

architects,

heritage consultants,

hydraulic engineers,

civil engineers,

landscape architects,

arborists,

environmental specialists,

local government development planners,

lawyers including Queens’ Counsel,

establishing a full-time staff of qualified horticulturalists, and

landscape specialists with skills to manage a complex site.

Our challenges extended to communicating with concerned members of the Leura community; state Government officials to the level of Director-General and Ministers; Court officials from the Land and Environment Court of NSW; together with the Chief Justice of the Federal Court; and members of Council including the Mayor, Councillors, and senior officers, on matters arising in responding to advocates holding a different viewpoint from our family.

Maintaining a garden of the scale of The Braes is not without many demands. Some elements of heritage assessment are also not without their challenge.

The work has been arduous, the challenges, often seemingly insurmountable, but the joy the garden brings to so many and indeed to our family has made every difficult step of The Braes revival and restoration more than worth it.